Iron Muse Photography of the Transcontinental Railroad

Glen Willumson 2013 178 pages (242 with notes)

Hundreds of photographs were taken of the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad by the Central Pacific Railroad, building west to east (CPRR), and the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR), building east to west. That’s not new. A lot has been written about the photographers and the construction of the railroad. Iron Muse is about the photographs, something which has not been done before.

Divided into only four chapters the book covers the general history, how the photographs were made and by whom, the development of the collections, and how the photographs were used. An epilogue finishes up things looking at how the use of pictures changed over time to accommodate societal changes.

Railroad buffs may be happy having a lot of old photographs to peruse but those photos have been reproduced countless times before and any railroad buff “worth his/her salt” will have seen them. This book stands out because it is about the analysis of those photographs.

What choices did the photographers make as they memorialized the railroad in each picture? What were the titles bestowed on the pictures and why? How were the photographs used and by whom? How were the photographic archives built by each railroad? What was included and how were they used by whom? Who were the various audiences for the individual photos and for the collections? Then in the epilogue Willumson shows how the meaning conveyed by select photographs changed over time to meet the needs of current public thought or politics. All of that went into what the public saw in transcontinental railroad photographs during the mid 19th Century, the 20th Century, and what we see today. That’s one set of questions. Another set of questions has to do with the negative. What was not photographed and why? What was left out of the archives and why? For example, the Chinese were the heroes of half of the transcontinental effort but in the celebratory photographs of the completion, they were, to us, conspicuously absent. People at the time saw nothing wrong or awkward with that. Nobody even mentioned it. They were busy celebrating the achievements of the White race in its various forms.*

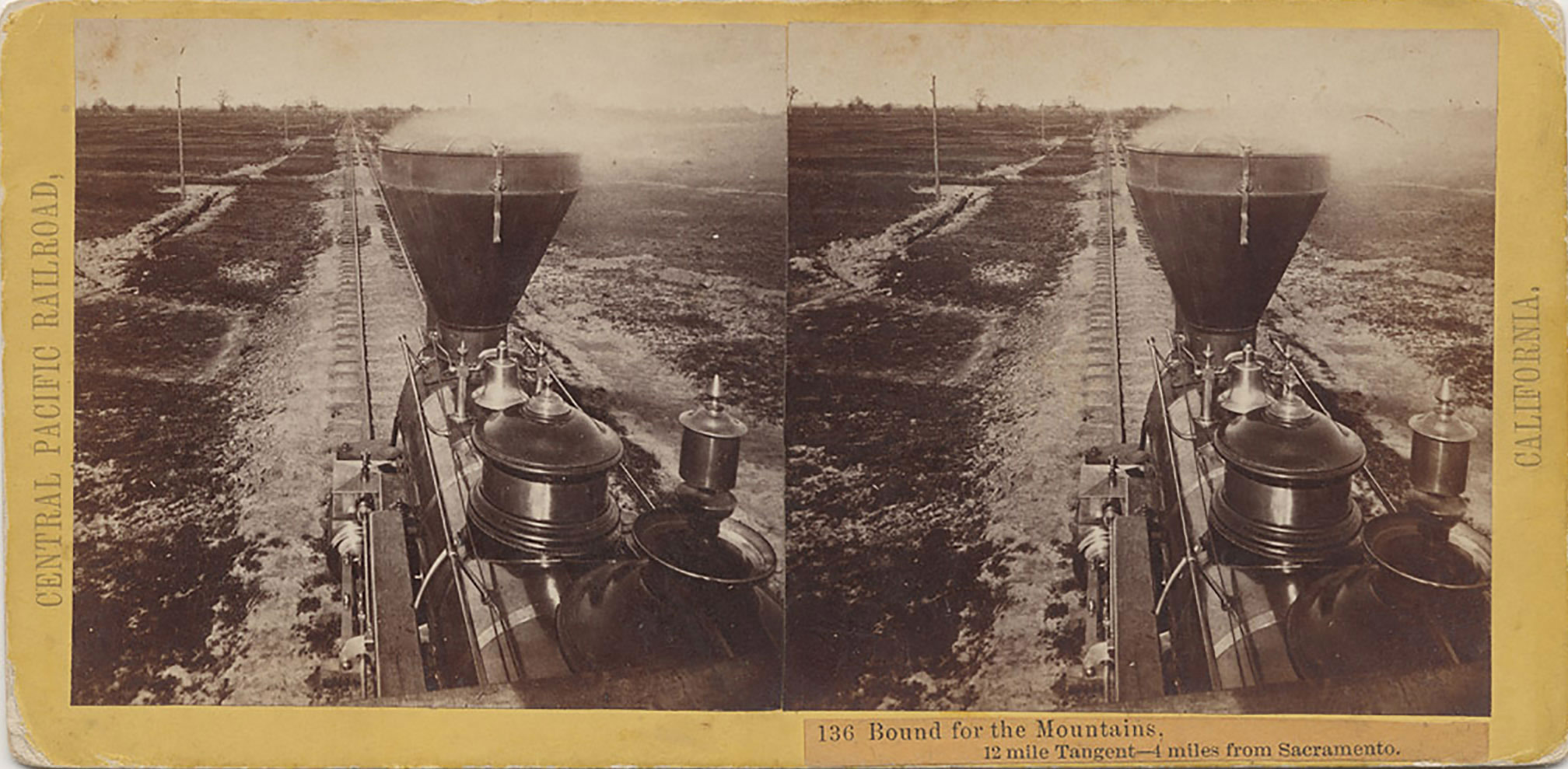

For an example of Willumson’s analysis of photographs look at Alfred A. Hart’s #136, “Bound for the Mountains.” For the amateur transcontinental photographic viewer this is another photograph of a locomotive and track. The transcontinental railroad is being built. Willumson, though, who is a professional transcontinental photographic viewer, delves into the photograph. The standard view of a train is on ground level at right angles to the track and train. Willumson sees Alfred A. Hart as a master though. He did it differently. He climbed up on the locomotive and behind it for his view. He looked down the track, taking “advantage of the formal qualities of spatial recession inherent in the stereograph. His efforts created a dynamic composition that approached the metaphoric.” He dragged “his heavy camera equipment up and onto the roof of the locomotive cab and composed the scene on the ground glass at the back of the camera.” Willumson says that cameras and film of the time could not capture motion but Hart simulated motion with his perspective. Most of us amateurs would enjoy the photograph and the detail but would not know why or appreciate the reasons behind Hart’s art.

For an example of Willumson’s analysis of photographs look at Alfred A. Hart’s #136, “Bound for the Mountains.” For the amateur transcontinental photographic viewer this is another photograph of a locomotive and track. The transcontinental railroad is being built. Willumson, though, who is a professional transcontinental photographic viewer, delves into the photograph. The standard view of a train is on ground level at right angles to the track and train. Willumson sees Alfred A. Hart as a master though. He did it differently. He climbed up on the locomotive and behind it for his view. He looked down the track, taking “advantage of the formal qualities of spatial recession inherent in the stereograph. His efforts created a dynamic composition that approached the metaphoric.” He dragged “his heavy camera equipment up and onto the roof of the locomotive cab and composed the scene on the ground glass at the back of the camera.” Willumson says that cameras and film of the time could not capture motion but Hart simulated motion with his perspective. Most of us amateurs would enjoy the photograph and the detail but would not know why or appreciate the reasons behind Hart’s art.

Willumson does not just analyze the photographs of the transcontinental railroad but also other forms of art: woodcuts of photographs and paintings. In all of his analyses he brings the reader more of the story. Typically we look at the old photographs and paintings or woodcuts and see them as records of what happened. Willumson’s analyses brings out the details and to our appreciation of the art grows and with Willumson’s instruction, we can begin to look for more in old photographs ourselves.

For example Willumson dissects “American Progress” from Crofutt’s Western World (1873). Here we have the movement west of the explorers, pioneers, wagon trains, and stagecoaches. The Native Americans and the wildlife are scattering before the coming of civilization. That’s obvious and an allegory of Manifest Destiny – America conquering the continent. In various forms we’ve seen it all before. Willumson goes a step further into what is hard to see. The allegorical figure of the female is in the sky overseeing what is being accomplished. “In her right hand she hold a schoolbook, and from the crook of her arm dangles a telegraph wire. The wire originates from the Brooklyn Bridge, which… as a reminder of the technological accomplishment and an insinuation that forces directing American progress flow out of Ne York.” Clearly education and technological progress go together. The painting idealizes “advancement from east to west.” That kind of analysis, helping the reader see detail that is not obvious, adds to the reader’s understanding and enjoyment. Willumson does that over and over. Then he cements his ideas with summaries, “Hart’s stereographs depict the railroad by bringing life to an otherwise sterile landscape and as a harbinger of European-American civilization.”

For example Willumson dissects “American Progress” from Crofutt’s Western World (1873). Here we have the movement west of the explorers, pioneers, wagon trains, and stagecoaches. The Native Americans and the wildlife are scattering before the coming of civilization. That’s obvious and an allegory of Manifest Destiny – America conquering the continent. In various forms we’ve seen it all before. Willumson goes a step further into what is hard to see. The allegorical figure of the female is in the sky overseeing what is being accomplished. “In her right hand she hold a schoolbook, and from the crook of her arm dangles a telegraph wire. The wire originates from the Brooklyn Bridge, which… as a reminder of the technological accomplishment and an insinuation that forces directing American progress flow out of Ne York.” Clearly education and technological progress go together. The painting idealizes “advancement from east to west.” That kind of analysis, helping the reader see detail that is not obvious, adds to the reader’s understanding and enjoyment. Willumson does that over and over. Then he cements his ideas with summaries, “Hart’s stereographs depict the railroad by bringing life to an otherwise sterile landscape and as a harbinger of European-American civilization.”

Willumson does the same with the archives. He explains how they were used and why and what was included and what was not. That’s a detail almost all viewers would not even consider as they page through old photographs. There is much more than just the composition and the taking of the pictures. There is the editing of the larger scene by leaving views and photographs out of collections. Willumson shows how some photographs were left out of the railroad collections as the railroads edited the story they wanted to tell, but appeared in public anyway elsewhere. He also shows how the photographer or woodcut artists made slight changes so the photographs could serve other purposes. For example, the snowsheds are iconic on Donner Summit and a technological solution to a pressing problem. They deserved photographing. The CPRR, though, didn’t want the public or investors to see that snow was such a problem and so, generally left those pictures out of their archive. Willumson says, “The Central Pacific purchased stereographs that conveyed a message of progress in the railroad construction; it disregarded other subject matter and suppressed any images that might suggest difficulties of construction.” Snow was one of the awkward “difficulties” and Willumson has a letter to prove the CPRR curated snow pictures right out of its collection, Charles Crocker writing to Colis Huntington, “… I shall not of course have any printed” of snow at Cisco. Willumson shows how the curating extended to the titles on photographs. Titles changed over time and for different purposes. Titles included details to impress the public with the technological challenge of the railroad giving the elevation or the depth of a cut (50 feet deep is impressive). “The Central Pacific titles build on the visuality of the stereographs, relying on the public perception of the photographs as truthful copies of reality calling attention to facts and data not available in the images, and using the authority of scientific measurement to reinforce the photographic messages.”

As with any analysis of literature in prose or poetry, or analysis of art, the analysis can go too far and Willumson does a few times. For example in analyzing a Harper’s Weekly illustration, “The Pacific Railroad” which shows passengers in a Palace Hotel Car, Willumson says, “They travel on the railroad in luxury while a uniformed African-American waiter serves them. In this engraving the new black citizens freed by the Civil War are indentured anew, serving the white passengers as they had their white masters before the war... Here the cultural force of the train creates harmony by reinforcing America’s prewar social and racial hierarchy… the message of the engravings proves to be the more accurate depiction of the tensions and inequality that would continue throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century.” That sounds a bit like bringing one’s own prejudices into the analysis. There can be a fine line between exploitation and honest employment. Railway jobs were one of the few ways black workers could be paid their worth and rise in post-slavery America. There is nothing wrong with serving others and just because one does, does not mean he’s being indentured anew. After all, indenture precludes escape. Railway workers could leave when they chose. Just because there were few other equal opportunities does not mean they were “indentured anew,”

In another example, Willumson says under a photograph of a railroad train meeting a wagon train that the viewer can “read this stereograph not only as a symbol of technological progress but as an allegory for the monopolistic capitalism that the Central Pacific had begun well before the completion of the railroad… the ceremony at Promontory was not the final act but only the latest skirmish in a monopolistic war over the control of rail commerce in the West.” Certainly the railroad became rapacious and even evil as Frank Norris’ The Octopus was just one example. But was that the case already at Promontory or is Willumson bringing in his own prejudices perhaps formed by later history? Perhaps Promontory was a celebration of technology with the negative ramifications of the coming of the railroad to be felt later and the abuses also to come later.

Iron Muse has a different emphasis from other books about the transcontinental railroad. The perspectives offered give a better understanding of this 19th Century technological wonder. They also provide enjoyment to the reader as she reads the analyses. That deeper view may carry over to other photographs in other collections later and so provide ongoing enjoyment.

Making a Picture – ca. 1869

Set up the camera

Climb down to his portable darkroom

Prepare the glass plate negative (hold the glass negative by one corner and pour collodion over the surface of the plate, rocking it to get an even coating

Place the plate in a holder

Dip the holder into a bath of silver nitrate

Put the prepared plate into a holder to protect it from sunlight

Climb back up to the camera and slide the plate into it.

Remove the lens cap and count the exposure

* The San Francisco Bulletin reported Judge Nathan Bennet’s speech at the San Francisco celebration. He said this triumph of railroad construction was wholly owing to the fact that his fellow Californians were “composed of the right materials, derived from the proper origins… In the veins of our people flows the commingled blood of the four greatest nationalities of modern days. The impetuous daring and dash of the French, the philosophical spirit of the German, the unflinching solidity of the English, and the light-hearted impetuosity of the Irish, have all contributed each its appropriate share… A people deducing its origins from such races, and condensing their best traits into its national life, is capable of any achievements.” It was stirring.