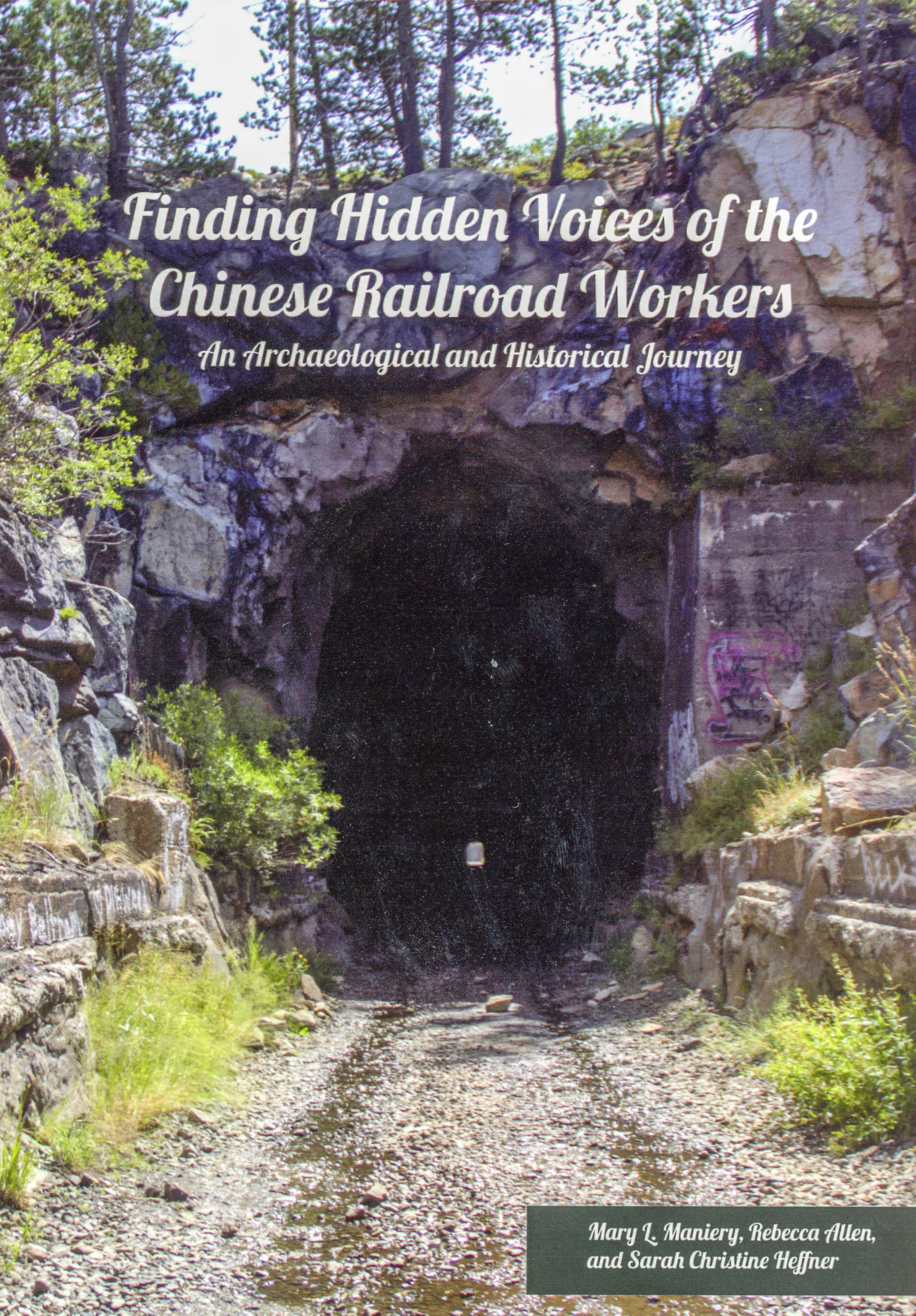

Finding Hidden Voices of the Chinese Railroad Workers -

An Archeological and Historical Journey

In association with the Chinese Railroad Workers Project at Stanford University and the Chinese Historical Society of America.

Mary Maniery, Rebecca Allen, Sarah Christine Heffner

2016 107 pages

The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in the mid-19th Century was the greatest industrial project of the age. Nothing like it had ever been done in the world. Without the Chinese railroad workers it could not have been done. Finding the Hidden Voices… is a wonderful overview of the Chinese contribution to that effort. The book is aimed at the widest audience, rather than an academic one, and to accomplish that it is done in a popular and attractive magazine-type layout style with, as the introduction says, a “vibrantly illustrated format” for the “diverse audience” it is aimed at. Prose is in short snippets.

Every aspect of the Chinese working on the railroad is reported: the project in general, the crews, dress, food, the work, work camps, health and medicine, recreation, legacy, etc. There is also some of the archeological work that developed a lot of the information and some of the archeology methods.

To help tell the story the book is illustrated with quotes, maps, pictures of artifacts, historical and modern pictures, illustrations, and ads. The historic pictures are a particular strength of the book as are the contemporaneous quotes such as, “We passed hosts of Chinamen… They are all young, and their faces look singularly quick and intelligent. A few wear basket hats; but all have substituted boots for their wooden shoes, and adopted pantaloons and blouses.” (Albert Richardson, New York Tribune, 1869 pg 27). There is even a little caption of a catfish picture saying that fish, planted by the Chinese, have survived and propagated for more than 140 years despite Sierra snows and ice. That of course is Catfish Pond on Donner Summit. At the end there is a good list for “further reading.”

The Chinese workers were not just the footnote that many histories of the Transcontinental Railroad relegate them to. They were integral and this book puts them at the center of the endeavor. The Chinese left no records themselves of their lives and work and so we have to rely on newspaper articles, reports by the railroad and visitors to work sites, and the archeological work to tell the stories. The many pictures of artifacts uncovered during archeological work illustrate the Chinese experience and the archeological component. For example in maps of Chinese work camp sites, done by archeologists, the reader can see how archeologists work. The artifacts illustrate what the text says about Chinese. They used porcelain from China rather than, or in addition to, America-made goods. They used coins for gaming and in folk medicine. Opium was used on the line. Some porcelain-ware was personalized with names. There is even a short discussion of the origins of different porcelain designs.

It’s important that Finding the Hidden Voices…. puts the Chinese contribution into perspective. In doing that it puts some of our past into perspective. There is a reproduction of an article titled, “Honors to John Chinaman.” The article says that upon completion of the railroad the CPRR’s chief engineer, James Strobridge, invited representatives of the Chinese workers to his railcar for a celebratory dinner. To the wider public the Chinese still remained anonymous and referred to as “John Chinaman.” History, the authors say, remembered the “Triumph of the line” and not the Chinese who “helped to link the East to the West.”

In 1928, things had not changed. The Southern Pacific (the Central Pacific had been absorbed) Bulletin (Vol. 16, no. 5, pg 3) said “Fifty-nine years ago a squad of eight Irishmen and a small army of Chinese coolies made a record in track laying that has never been equaled…” “Fired with enthusiasm” the team laid ten miles fifty-six feet of track in one day.

“The names of the Irish rail handlers have been passed down through the years. Their super human achievement will be remembered as long as there is railroad history.” With no note of irony, because it was expected at the time, the article continued, “So, too, will that day’s work of ‘John Chinamen” be recalled as the most stirring event in the building of the railroad.” Chinese workers weren’t worthy of having their names remembered and indeed were not even considered as individuals by the railroad. More likely they were hired in groups with their names lost to history.

One would think that as modern times arrived the story would have changed. But on the 100th anniversary of the completion of the railroad in 1969, a celebration was held. The Chinese Historical Society of America moved to ensure recognition of the Chinese contribution. They had two commemorative plaques made to install during the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah. The plaque dedication was not include in the official program although the Historical Society received a telegram saying that a spokesman for the “Chinee [sic] Community would be on the platform. During the ceremony, when no Chinese were allowed to speak, the Secretary of Labor, John Volpe, said, “Who else but Americans could drill ten tunnels in mountains thirty feet deep in snow? Who else but Americans could chisel through miles of solid granite…” Who else indeed, except the Chinese who did do the tunneling of fifteen tunnels and did chisel through solid granite.

Hidden Voices can be obtained at Lulu.com

For more information about the Chinese and Donner Summit:

June - September, '16 Heirlooms

Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University