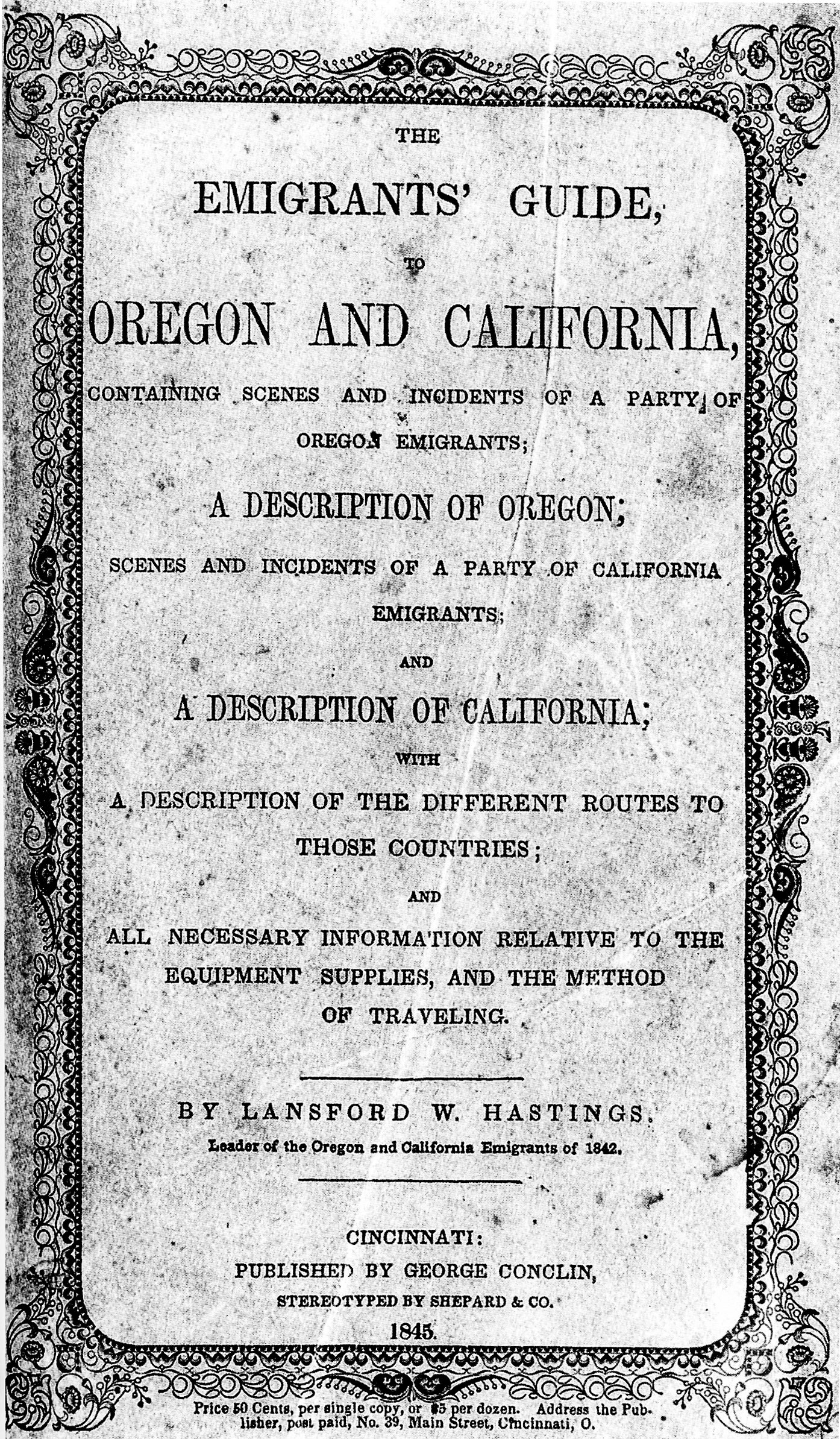

The Emigrant’s Guide To Oregon and California in 1845

The Emigrant’s Guide To Oregon and California in 1845

Lansford Hastings

265 pages

Being in the area of Donner Pass* I’ve always wondered what it was about Lansford Hastings’s book, The Emigrant’s Guide, that lured the Donner Party into taking the left hand turn. The “short cut” slowed them down so they arrived at Donner Pass when there were feet of snow on the ground. They couldn’t get over Donner Summit. They were trapped. The more I read about Hastings in other Donner Party books (see our book review page or Heirloom indices) the more questionable he looked. The book has been on the DSHS ready to review book shelf for some time. Here, maybe, we answer the question.

First a little background.

James Reed, Donner Party personality who was expelled from the group after killing another member and who got to California early and started rescue attempts, said, “The new road, or Hasting’s Cutoff is said to be a saving of 350 or 400 miles in going to California and a better route.” He hoped it would be seven weeks to Sutter’s Fort, 700 miles on the “fine level road, with plenty of water and grass.” On July 31 the party turned onto the Hastings Cutoff, leaving the California Trail almost everybody else was taking.

Six days later the wagon train found a note from Hastings. He said the road ahead was almost impassible. James Reed rode forward to meet Hastings and get help with an alternative. Hastings came part way back and pointed to another way, one he’d also never been on. It was terrible. . There was no trail to follow. They only two miles a day and had to cut their way through the wilderness

Two weeks later there was another note. It would only take two days to cross the desert in front them. That was also bad advice. It took five days. It was 80 miles across not 40. Water ran out. Oxen ran away. People were exhausted.

When the Donner Party left the Hastings Cutoff, the “short cut” and rejoined the California Trail they’d gone 125 miles farther than and spent weeks doing it. The Donner Party spent 68 days on The Hastings Cutoff while other parties spent 37 days on the California Trail to get to the same point .

James Reed’s daughter, Virginia, wrote, “O Mary I have not wrote you half of the truble but I hav Wrote you anuf to let you now what truble is but thank the Good god and the onely family that did not eat human flesh we have left everything but I don’t cair for that we have got Don’t let this letter dishaten anybody never take no cutoffs and hury along as fast as you can.”

The Donner Party was late to the Sierra. They missed the turn to Coldstream Canyon and were trapped at what would soon be called Donner Lake, just below Donner Pass. The Hastings Cutoff, among other things, was the undoing of the Donner Party.

Hastings was part of a party going to Oregon and then he led a party to California in 1845. In 1846 he went back to Fort Bridger to greet emigrants and steer them to California. There he picked up 60 wagons and headed back to California leaving notes for following emigrants to take his trail. The Donner Party was just a bit behind and missed connecting to Hastings. Those who did go with Hastings made it to California.

The Emigrant’s Guide was more of a sales brochure than a guide to get to California. It was a very long sales brochure though (232 pages of the 265) that extolled the virtues first of Oregon and then California.

The first few chapters, 110 pagers, focus on his trip to Oregon, a narrow escape from Indians, and descriptions of Oregon, but since most readers here are not headed to Oregon in 1845 we can dispense with it. Besides, the lists and statistics are a bit tedious.

More of the book is about “that highly important country” Upper California (only Upper California because of the “extremely narrow limits of this small work”). Hastings’ Upper California extends from the Pacific all the way to the Rockies (this was before the Mexican War when the area was all one big territory belonging to Mexico). Here again there is tedium. Hastings lists landmarks without names but with latitude and longitude and other information. Without names or Google Earth nearby the modern readers is lost.

Beyond the lists all of Hastings’ descriptions of California are in the superlative. The climate is in perpetual spring. There is snow in some places but lasts only two or three hours. “No fires are required, at any season of the year…” Vegetables are planted and gathered at any season. There are two grain crops annually. “Even in the months of December and January, vegetation is in full bloom.” “December is as pleasant as May.” In the mountains of course it’s different so “You may here enjoy perennial spring, or perpetual winter as your options. You may in a very few days, at any season of the year, pass form regions of eternal verdure to those of perpetual ice and snow.”

Such a good climate promotes health, “There are few portions of the world, if any, which are so entirely exempt from all febrifacient causes… no… noxious miasmatic effluvia…The purity of the atmosphere, is most extraordinary, and almost incredible. So pure is it, in fact, that flesh of any kind may be hung for weeks together, in the open air, and that too, in the summer season, without undergoing putrefaction.” “…disease of any kind is very seldom known…” Any sickness is mild and so people seldom resort to medical aid. People were unanimous that “…this is one of the most healthy portions of the world… few portions… are superior… in point of healthfulness and salubrity of climate.”

Heavy timber stands abound with trees being 250 feet high and 15-20 feet in diameter. A multitude of crops are grown. The “climate and soil, are, eminently adapted” to grow almost anything and here Hastings lists a couple of dozen kinds of crops. It’s so easy to grow things that all a farmer has to do is “designate a certain tract as his oat field, and either fence it, or employ a few Indians” and he reaps a crop. Besides all the delicious fruits there is wine “which always constitutes one of the grand essential of a California dinner” and here Hastings noted that his temperance pledge did not include wine.

There are immense herds of animals too and domestic animals can be reared “with little, or no expense. They require neither feeding nor housing and are always sufficiently fattened….” Horses are found in “herds almost innumerable, and they are always in the best condition” so they can be ridden or driven for days without food or rest. “…cattle are much ore numerous then [sic] the horses; herds of countless numbers are everywhere seen… farmers have, from twenty to thirty thousand head.”

There is game of every description and he lists more than a dozen and this provides us with a wider view of mostly pre-settled California. There are herds of elk and antelope. Wolves are so numerous that it’s a waste of ammunition to kill one. There are bear, both grizzly and brown. The “fur bearing animals are much more numerous… than in any other section of the country…. Especially the beavers, otters, muskrats and seals.” At some times of the year “the whole country, [is] literally covered with the various water-fowls…” One could fill a feather bed “in a very few hours.” The noise of “innumerable flocks” can be deafening “blackening the very heavens with their increasing numbers…” with “tumultuous croaking and vehement squeaking.”

The fisheries “are unusually plentiful.” Hastings lists ten species and then moves on to shell fish which “abound… in great profusion.”

For all the wealth of natural resources and agriculture there was an ample market that could absorb all resources so emigrants to California could be assured of success. Better yet, there were no price fluctuations in markets as there were in the United States.

Although California was an “infant country” its commercial prospects were “scarcely equaled” and in a few years would “exceed, by far, that of any other country in the same extent and population, in any portion of the known world.” “In a word, I will remark that in my opinion, there is no country, in the known world, possessing a soil so fertile and productive, with such varied and inexhaustible resources, and a climate of such mildness, uniformity and salubrity; nor is there a country, in my opinion, now known, which is so eminently calculated, by nature herself, in all respect, to promote the unbounded happiness and prosperity, of civilized and enlightened man.”

Hastings goes on to describe other aspects of California and then gives some insight into the 19th Century mind. He was clearly anti-Catholic and castigates the missions and the “despotic and inhuman priesthood” which have huge resources and “palace like edifices” to accommodate “religious oppressors” who have “keys of both heaven and hell” and who are the “authorized keepers… of the consciences of men” but who enslave and oppress the “unsuspecting aborigines” and the “lower orders of the people, to a most abject state of vassalage.” He goes on with anecdotes of priestly perfidy.

The population of California, according to Hastings, was about 31,000 people of whom 20,000 were Indians. The “foreigners’ in California were almost exclusively from the United States and were “generally, very intelligent… and they all possess an unusual degree of industry and enterprise.” They are even of better quality than others who “ emigrate to our frontier. They possess more then [sic] an ordinary degree of intelligence, and… possess an eminent degree of industry, enterprise and bravery” just because they’ve gotten to California. No one will embark on so “arduous and irksome” a feat as to come to California without the “requisite” bravery, strength, and more than “ordinary share of energy and enterprise.”

Not only do the residents of California have such “leading traits of character” but they have “extraordinary kindness, courtesy and hospitality… A more kind and hospitable people are nowhere found… Here… the citizens and subjects, of almost every nation in the civilized world, [are] united by the silken chains of friendship.”

Mexicans were different though. The Mexican character was composed of ignorance, superstition, suspicion, and superciliousness. “More indomitable ignorance does not prevail… they are scarcely a visible grade, in the scale of intelligence, above the barbarous tribes by whom they are surrounded…” The reason for that was intermarriage with the Indians. Hastings said you can not tell the difference between those of mixed race and Indians in intelligence or appearance. Hastings describes the hierarchy from top to bottom: Americans, Europeans, Mexicans, the mixed races, and “the aborigines… who have been slightly civilized, or rather domesticated.” [Hastings’ italics]

Having introduced the marvelous country of California in 132 pages (leaving out the Oregon part), it was time to guide the emigrants to California. Having heard of Lansford Hastings and his Emigrant’s Guide I’d always thought that it was an emigrant’s guide for getting to California and not a guide book of California. It turned out though, that it is mostly a guidebook of. Oregon and getting there takes up 100 pages or so. The guidebook of California takes up 130 pages or so. The guide getting to California is only 30 pages or so and most of that is taken up with what to take, how to travel, lessons for traveling by wagon t rain, etc.

There is only a single sentence in the guide for getting to California that would lead the emigrants, like the Donners, astray. Hastings suggests emigrants leave the main route short of Ft. Hall “thence bearing west southwest, to the Salt lake [sic] and thence continue down to the bay of St. Francisco…” Emigrants had the guidebook and having read of California’s wonders, they were salivating at the prospect of getting there. No doubt they discussed California over their campfires. They knew that Hastings was waiting at Ft. Bridger since news traveled along the trail. They were probably disappointed that they’d missed Hastings when they arrived, but they were excited, and when they saw Hastings had gone a different route from the one taken by most wagons, they went after him. Unfortunately Hastings had never been on his new route.

In the last part of the guide Hastings considers the different routes to California and after analysis, recommended the route over the Sierra, Donner Summit. The route was 2100 miles and should take, Hastings said, 120 days. In particular it was so much easier than the trip to Oregon.

Here, in describing the route emigrants should take, Hastings exaggerates the easiness, “Wagons can be as readily taken from Ft. Hall to the bay of St. [sic] Francisco, as they can, from the States to Fort Hall; and, in fact, the latter part of the route, is found much more eligible for a wagon way, than the former.” That route lay over plains, valleys, and hills, and amid “lofty mountains; thence down the great valley of the Sacramento, to the bay of St. Francisco.” The Indians, he added, were “extremely timid and entirely inoffensive.”

The route sounds like a sightseeing trip and California, the land of dreams, was just down the road. Thousands of emigrants would object to Hastings’ characterization. Crossing the desert in Nevada was excruciating. People and animals died. The heat was almost unbearable. People left behind not just treasures but things needed to start life in California because they could carry them no further. Emigrants would also have objected to Hastings’ characterization of the Indians too who often stole or wounded livestock, the wounded having to be left behind for the Indians.

Having barely survived the desert emigrants next approached the Sierra. That was not just traveling among “lofty mountains.” The Sierra was hardest part of the entire trip. Emigrants looked with terror at the looming mountains. How cold they be so close and yet so far? How would they get over the Sierra. They must have cursed Hastings. At least one might expect that at the top it was all downhill from there to California. It wasn’t. It was almost as bad as the east side going up.

The emigrants did not know all that of course when they picked up Hastings’ book. Since it was filled with so much detail about California and so much seemingly good advice about traveling in a wagon train, his credibility was assured and people followed. So when he left notes behind as he traveled west in 1846, some people reasonably followed them.

*Because the Forlorn Hope and the rescuers of the Donner Party went over Donner Pass and Starved Camp was somewhere in Summit Valley we can cover the subject.