Carleton Watkins Making the West American

Tyler Green

2018 574 pages

Carleton Watkins was one of the official photographers of the Central Pacific railroad and so took a number of pictures on Donner Summit. In our December, ’16 Heirloom we reviewed Carleton Watkins the Complete Mammoth Photographs. It included photographs of Donner Summit but it was about the mammoth photographs Watkins took and was not a biography. So you can imagine our excitement when Carleton Watkins Making the West American was published. Here we’d have the life of one of the many artists who visited Donner Summit and left a mark in the art he did.

There are two problems here. One is that there is virtually nothing in the book about Donner Summit, the first transcontinental railroad, or the pictures Watkins took on Donner Summit and nearby (or parenthetically, his reprinting Alfred A. Hart photos of the railroad and Donner Summit with “Watkins” affixed). The second problem is that there is little about Watkins’ life. That second is not Mr. Green’s fault. The 1906 earthquake destroyed Watkins records and negatives among other things. We have no entry into the person who was Carleton Watkins beyond a kind of technical entry which is provided by his photographs and what various public records like newspapers say. We don’t know what he thought of the issues of the day, for example about California and the Union; how he met those who would influence or enable his work; whom he actually knew well; what the loss of his gallery and twenty years of work in 1875 meant and how he recovered; his marriage and children; the destruction of his gallery and work in the San Francisco earthquake; etc. It’s a huge hole in what should be a good, or anyway more complete, story especially given the contributions Watkins made. So what’s left for a biography if there is nothing about the person?

Green decided the way around the problem was “to learn about the world he [Watkins] inhabited and impacted and to place him and his work in it.” That he does. About Watkins’ life there are a lot of suppositions phrased as “would have,” “probably,” “maybe,” or “it is possible.” Since we can’t focus on Watkins’ life we focus on what Green filled this large book with: digressions about the world Watkins inhabited and impacted. Some of those subjects are Emerson and the transcendentalists; Thomas Starr King, the man who saved California for the Union; Jesse Benton Fremont (the wife of John Fremont); the birth of the national park idea and preserving Yosemite along with the wider social and political currents of the time, and how Gettysburg was a model; various historical figures and personalities; farming in Kern County; exploration of the west; science; the politics of the time; the development of the theory that glaciers carved Yosemite and other parts of the Sierra; Wm. Ralston (The man who built San Francisco); and saving California for the Union. So the reader gets a wider view than just a biography of one artist. It’s a big slice of the 19th Century.

This book is about Carleton Watkins, a famous 19th Century photographer. He was known nationwide and in Europe. Many 19th Century celebrities collected his work. His pictures hung in Capitol building and the White House in Washington D.C. One former president might even have stolen Watkins pictures from the White House. He won national and international awards. He helped set Yosemite aside for preservation. He made contributions to science, industry, architecture, and farming. He brought the scenery of California to the nation. Then he died penniless and forgotten in the State Hospital for the insane in Napa. Today, few have heard of him despite his contributions to California about which the author says, “…no single American did more to make the West as part of the United States, to join the remote new lands to the East, than Carleton Watkins… Watkins story is the story of the West’s maturation.”

The first part of the book traces what little is known about Watkins from his birth in New York in 1829 and his moving to California in 1849. Watkins knew Collis Huntington, one of the Big Four of the Transcontinental Railroad, and came to California with him by ship. Huntington clearly was a major figure in the transformation of California. Green says Watkins was on the same level, playing a starring role in the “rise of the American West and in the transformation of the nation from an agrarian coastal state to a continent –filling industrial power.” That’s high praise and book then proves the point.

It is not known what Watkins did on arrival in California. In 1853 he was a stationary store clerk in San Francisco. Where, how and why he learned photography we also don’t know but he perhaps read about it in the magazines he sold in the store. In 1856 he went to work for a short time with a photographer in San Jose. Photographers in those days did their work mostly indoors but with that background Watkins went on to work outdoors doing landscape photography and that is where he would become famous and accomplished “creat[ing] a series of photographs that changed American art and impacted the nation’s history.”

What really started Watkins on his own was a contract with John C. Fremont (explorer, first Republican presidential candidate – 1856, and California senator) to photograph Fremont’s estate in Mariposa. Fremont needed investors to fully develop the gold mining already being done on his property and the Watkins photographs helped sell the investments. It was at Jesse Fremont’s (John C.’s wife and the daughter of another U.S. senator) salons that Watkins met many famous Americans including Thomas Starr King. King “did the most to share Watkins’ work with the east.” King was a transcendentalist who loved the land so there was a natural connection between the two over California and Western landscapes. To begin with, Watkins photographs of Yosemite made him famous. For that he’d designed a camera to make “mammoth” photographs, 18” x 22”, something no one was doing and something that made the job much more difficult. In those days the glass negatives were the actual size of the later print which was made via contact printing (laying the glass negative on photographic paper and then introducing light).

Here we should say Watkins had ambitions to do more than other photographers: going outdoors which few others were doing, designing his own camera, and dealing with more complicated or difficult logistics. Each custom glass plate weighed 4lbs. His processes required triple the amount of chemicals of other photographers with their more modest photographs. His development equipment had to be larger and heavier too. All that he hauled all over California. He also hauled the camera, glass plates, and chemicals to prepare the negatives to sometimes almost inaccessible picture locations. For his 1861 trip to Yosemite he hauled in 2,000 lbs. of equipment. All that meant extra assistants. It was also a great risk because it was all expensive. He had to be confident he could recoup his costs with the sales of the resulting photographs.

Unlike other photographers whose pictures were turned into engravings for publication, Watkins “mammoth” photographs were framed to be put on walls. He saw his creations as art work, as did his many famous and well off customers. Here is the maturation of the art.

Watkins first pictures of Yosemite created a sensation and they went east to show Americans what the landscape in California looked like, as well as to prove the existence of redwoods.

Green says that Watkins’ work even has ramifications for today. His alliances with scientists, artists, and transcendentalists over the natural landscape “set an important precedent that continue to have an impact on the environmental movement to this day… and … lead directly to the emergence of the American conservation movement.” Green also makes an interesting point that at the same time Watkins photographs of Yosemite were being exhibited back east, people were also seeing, in juxtaposition, the exhibits of the horror of the Civil War raging at the time. That gave people positive feelings about the west and to give them a sense of hope.

Watkins pioneered the exposure of California’s diverse landscape to the rest of the world photographing Yosemite, the Sierra foothills, Mendocino, missions, architecture, Shasta, and the Sierra. He also photographed the Columbia River area, Montana, and Nevada. His photographs played a part in getting Yosemite preserved.

This is a biography and history book and so there are a lot of facts and analysis. Green inject humor every once in a while to show he’s not just an academic. For example, talking about President Johnson at his swearing in, Green says Johnson “gave an acceptance speech that Johnson probably should have given alone...” because he was drunk. About John Muir, “Perhaps one reason Muir felt at home in Yosemite was because the landscape was named after his friends” (by Muic). In talking about the controversy about whether glaciers carved Sierra topography, Green reprises the argument with Josiah Whitney (Mt. Whitney) being dismissive of the new theory and saying it was absurd and based on ignorance. Green has one comment on Whitney’s depicting the theory as stupid, “Meow.”

Watkins pictures were not just for display and enjoyment. Many of his pictures were the result of contracts to provide evidence in lawsuits, information for prospective investors, or to provide examples for scientific study such as trees, topography, or volcanoes. He photographed to provide records, for example of mining activity and property boundaries. His photographs of Yosemite were used by opposing scientists either to support evidence of glacial action, the now accepted theory, or of cataclysmic geologic events.

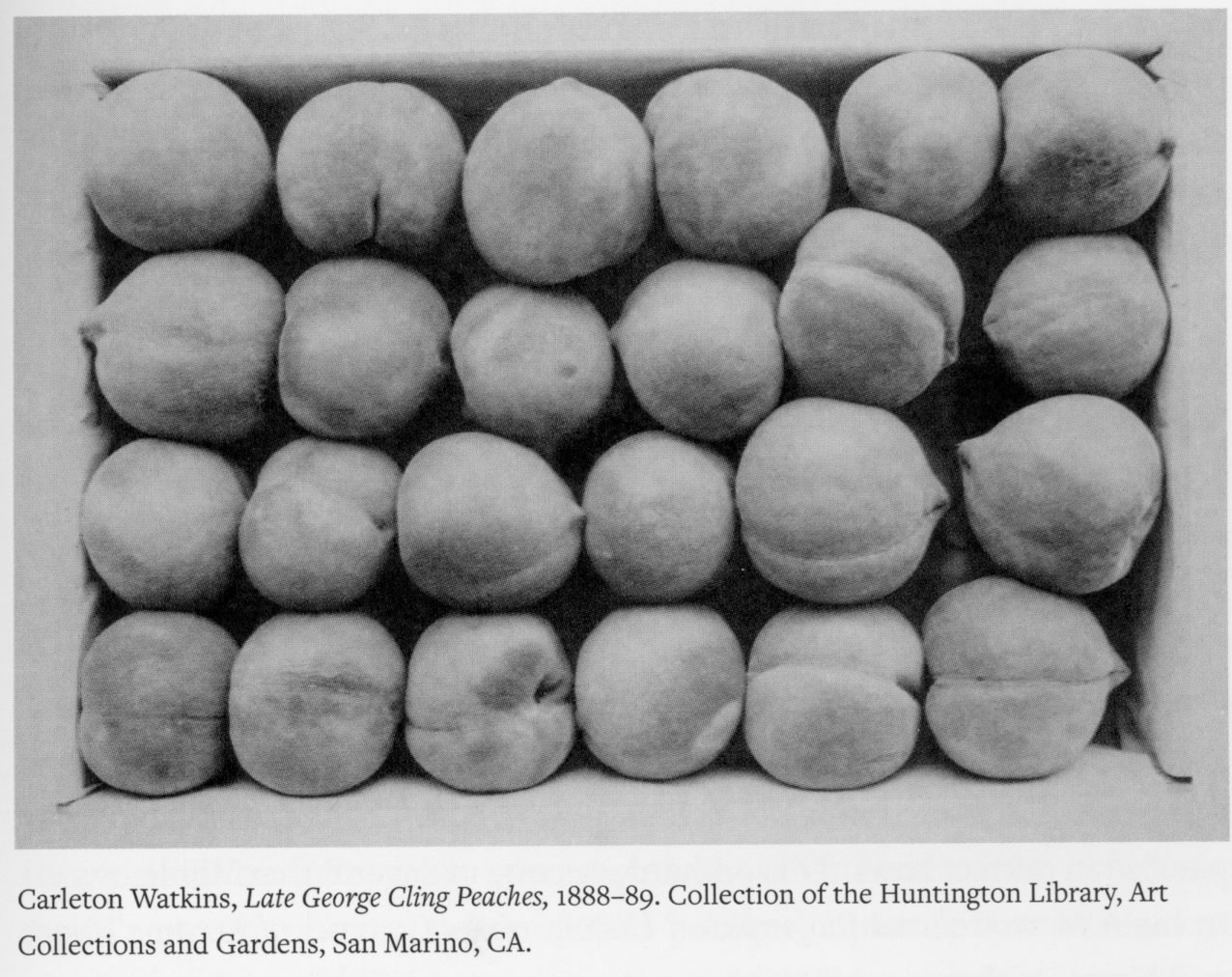

Green is an art historian and spends a lot of time, sometimes tediously, analyzing photographs, recounting visits, describing pictures, and examining detail. For example, Watkins did a lot of photographing in Kern County getting materials for a client to woo buyers. Green notes that but also goes into the artistry of the photographs putting them in the context of other artists (painters and photographers), what he needed to show and then how he did it. One example is a simple photograph of a box of peaches, “Late George Cling Peaches” which Green says was Watkins’ last great photograph. On one level this is a box of peaches showing the bounty of Kern County and how easy it would be for prospective buyers to make money but “so much about Late George Cling Peaches is unprecedented,” says Green in his analysis. Watkins could have done any number of things to show the bounty. He could have taken a picture of a lot of boxes, of trees full of fruit, etc. Instead he chose a straight on shot of the box, presenting the peaches in a grid, “a metaphor for western modernity.” This may have been the earliest grid in art and which became a ubiquitous form in art of the 20th Century. The picture also summarized modernity in the way that farm lands are delineated by grids which was how the railroads got the land from the Federal Government, how the land was sold, etc. Orchards were planted in grids and irrigation was done in grids. The grids were made possible by a new science, geodetic mapping to which Watkins had contributed with supporting photographs.

The box of peaches showed another bit of modernity. In 1889 the idea of shipping fruit was new. Previously it had not been possible and fruit was fermented or dried. The coming of railroads meant fruit could be shipped in boxes that protected the fruit and which could be stacked “…his box of peaches w[as] both reality and a metaphor for the newest, latest West.” “The picture is a thorough representation of a modern system, a new system of development, land ownership, irrigation, and transportation networks, of a new America made possible by the new West. The last great picture Watkins made [peaches] was of the West that his work had done much to realize.

The box of peaches showed another bit of modernity. In 1889 the idea of shipping fruit was new. Previously it had not been possible and fruit was fermented or dried. The coming of railroads meant fruit could be shipped in boxes that protected the fruit and which could be stacked “…his box of peaches w[as] both reality and a metaphor for the newest, latest West.” “The picture is a thorough representation of a modern system, a new system of development, land ownership, irrigation, and transportation networks, of a new America made possible by the new West. The last great picture Watkins made [peaches] was of the West that his work had done much to realize.

Green says Wm. Ralston was the man most responsible for initially building San Francisco into a “global urban center”, who made the gold mines into financial instruments, who bankrolled many industries, began the pivot from mining to agriculture in California, and “the man who had almost certainly been the primary enabler of California’s greatest artist,” Carleton Watkins. Ralston died by suicide in 1875 and Watkins got caught in the aftermath when his loans from Ralston were called in by their purchaser. Watkins lost his gallery in San Francisco, all of his equipment and his entire collection of photographic negatives. Since we have none of Watkins’ records or thoughts, we have no idea what the details were, how Watkins reacted initially, what he felt or what effects the tragedy had on him. At age 46 two decades of work were gone and now someone else could sell his “Watkins” photographs. Watkins would end up essentially competing with himself. A lesser man would have been crushed.

Watkins started over making use of his many contacts and former clients. He went back to his previous photo shooting locations and redid his work. It must have been difficult on many levels but Green analyzes the results and says Watkins came back with even better photographs. He also added locations: Lake Tahoe and Virginia City and here he makes a trip to the Sierra to photograph the Central Pacific Railroad. That’s about all the mention we get of that partly because details of Watkins’ life are missing. A big question, though, is that as he became the photographer of the Central Pacific in place of Alfred A. Hart, how did Watkins feel about “inheriting” Hart’s photographs, which belonged to the CPRR and putting his name on them? He must have been really aggravated to see his pre-1875 photographs sold without any recompense to himself. Here he did something of the same with Hart’s work. Green doesn’t address that at all.

Watkins married late to an employee of his gallery in San Francisco who was more than twenty years younger. Two children resulted. Here we get one small bit of personal history. Green says that Watkins daughter gave a date for Watkins’ marriage that was incorrect. Apparently the parents hid their daughter’s illegitimacy from her.

Towards the end of the 19th Century Watkins’ sight began to go. We don’t know how he dealt with that. Another tragedy hit Watkins on April 18, 1906 when the San Francisco earthquake destroyed his studio and work, ironically just the day before his photographic plates, records, and a mysterious trunk full of historical items were to go to Stanford University. Watkins fell into poverty, became blind, apparently developed dementia, and was committed to Napa State Hospital for the insane. He died in 1916.

By 1870, Watkins “was already the artist who had contributed the most to American scientists’ understanding of the West. He was probably also the artist who had contributed the most to American science, period.” Tyler Green