“Let the pilgrim to these Sierra shrines… leave the beaten line of travel…Let him quit the scene where sawdust chokes and stains the icy streams….” Instead let him “Plunge into the unbroken forests — into the deep canons [sic] ; climb the high peaks ; be alone a while and free. Look into nature… [it] will make a man better, physically and mentally. He will realize from it… the value of high mountain exercise in restoring wasted nervous energy and reviving the zest and capacity for brain work. He will find in it a moral tonic… and come back to the world… more patient and tolerant, more willing to… work.”

Benjamin Avery

Californian Pictures in Prose and Verse

Benjamin Avery 344 pages 1878

To get an idea of what it really was like in the old days: what people did how and why, how they lived, what the ramifications are for today, why we do what we do, etc. we can read history texts. Then we have to rely on what the author chooses to tell us, what facts she decides are important, what their meanings are, and of course we have to navigate author prejudices or preferences. History texts are good – the Heirloom is one example. It can also be useful and fun to read primary texts – what people wrote at the time. We have to navigate those prejudices too and they can be substantial, but those prejudices help tell us about history too. Reading initial reports of the Donner Party, for example, tell us that people in those days were just like us today. The telling is lurid and would fit well in today’s supermarket tabloids and “fake news” outlets.

That’s by way of explaining why this month’s book review is of a 19th Century book. Californian Pictures in Prose and Verse is a slice of time in California, written for armchair travelers, about the wonders of California. It must have made readers wish they too could trace Benjamin Avery’s travels. My copy of the book came from New York (besides used books there are also a number of variations of ebooks you can access for free.) I can imagine a previous owner of my copy of Californian Pictures… sitting in his study in New York City, brandy in one hand, book in the other, a fire in the fireplace, dog curled up on his slipper-covered feet, imagining traveling to California, entranced by the wonders Avery describes.

In general, one has to like words to delve into 19th Century literature. It was a different time and things went at a slower pace. The vocabulary is richer and the sentence structure more complicated. Delving into Avery’s book is like that. His descriptions are amazingly evocative. For example, here, after describing Castle Peak and the climb to the summit, Avery says, “grass and flowers grow luxuriantly, and swarms of humming-birds hover over the floral feast, their brilliant iridescent plumage flashing in the sun, and the movement of their wings filling the air with a bee-like drone.” Don’t you wish you could be there? Coming up the “Western Slope” on the train, Avery must have gotten off the train for a walk, “Once more the quail is heard piping to its mates, the heavy whirring flight of the grouse startles the meditative rambler, and the pines give forth again their surf-like roar to the passing breeze, waving their plumed tops in slow and graceful curves across a sky wonderfully clear and blue.” You don’t rush through prose like that; you slow down, savor it rolling the words around on your tongue, and imagine the images.

There are only 13 traditional pictures or drawings in this book because the book is not a picture book in the traditional sense. The other 331 pages are full of pictures in prose, like the ones above, and verse, describing California and of course, Donner Summit. Avery called them “word sketches” or “pictures in rhyme.” Section after section is described by Avery in “word sketches” as evocative as actual pictures. For example, he visited Summit Soda Springs, the original Soda Springs on Donner Summit, and took a trip to the top of Tinkner’s Knob “(named after an old mountaineer, with humorous reference to his eccentric nasal feature)… Clambering over the broken rock to the top of Tinker's Knob a magnificent panorama is unfolded. Over three thousand feet below winds the American River, — a ribbon of silver in a concavity of sombre green, seen at intervals only in starry flashes, like diamonds set in emerald.”

Taking the train to Truckee Avery says, “The descent to Donner from the granite peaks at its western end is abrupt and rugged, and the view from those peaks is remarkable for its stern grandeur.” Then at Lake Tahoe, “The transparency of the water is so great that small white objects sunk in it can be seen to a depth of more than one hundred feet. Sailing or rowing over the translucent depths, not too far from shore, one sees the beautiful trout far below, and sometimes their shadows on the light bottom. It is like hovering above a denser atmosphere.”

Avery wrote a number of books and magazine articles (for Overland Monthly for example) about his travels (see also “Summering the Sierra” pts. I and 2 in the June & August, ’11 Heirlooms for example.) He begins Californian Pictures…. with a description of California’s two mountain ranges, the Coast Range, separated by the Golden Gate, and the Sierra Nevada. The he goes on to the Central Valley and large and small lakes, passes, etc. This inventory of topographical diversity acquaints the reader with the richness of California and sets up the narrative for the focus on specific areas. There’s nothing surprising here for us because the geography has not changed.

Moving into the mountains, Donner Summit is first mentioned when noting that a forerunner of PG&E, the South Yuba Canal Company had dammed Meadow Lake (north of Fordyce) and, near Devil’s Peak, was using Devil’s Peak Lake (today’s Kidd Lake) and nearby lakes. Water released from those lakes kept the So. Yuba flowing in summer before water was siphoned off downstream for mining. Presciently Avery notes that when mining stops the water would be used to “irrigate countless gardens and vineyards on the lower slopes of the Sierra.” Indeed, the canal companies were in trouble once the State Supreme Court outlawed hydraulic mining in 1884 (six years after this book was published). Fortuitously, orchards were being planted in the Central Valley and foothills providing a market for Sierra water. Lake Van Norden would fit into that scheme a bit later, but that’s a different story.

“Up the Western Slope” is “the grandest of all the mountain ranges on the western side of the United States”, the Sierra Nevada. “Probably the passage of no other mountain range of equal magnitude affords so much scenic enjoyment… as the Pacific Railroad make daily practicable.” One must leave the train, though, to enjoy the full experience, “a trip to the summit is especially striking for the sharp contrast between the Eden-like beauty of the lower country and the Arctic pallor of the region within the snow-belt.” Avery describes the beauty of train travel from Sacramento across the Sierra: “many-colored wild flowers”, most brilliant of which is the California poppy “deep orange cups flame out in sunny splendor where they are massed in large tracts,” mistletoe tangled in the “leafy tresses” of trees, birds making “gay scenes vocal with unfailing song. The atmosphere is singularly clear and pure;… The whole influence of the landscape and the season intoxicating. And the floral profusion… vernal dressing… honey breathing bloom…” But it’s not all beauty as the train passes the hydraulic mining areas.

“Here the chocolate-colored rivers, choked for a hundred feet deep with mining debris,

attest the destructive activity of the gold-hunters. Every ravine and gulch has been sluiced into deeper ruts or filled with washings from above. Lofty ridges have been stripped of auriferous gravel for several continuous miles together, to a depth of from one hundred to two hundred feet. Cataracts of mud have replaced these foaming cascades which used to gleam like snow in the primeval woods. And the woods have, alas ! in too many cases, been quite obliterated by the insatiate miner.

“But it is pleasant to observe how nature seeks to heal the wounds inflicted by man ; how she recreates soil, renews vegetation, and draws over the ugly scars of twenty years a fresh mantle of verdure and bloom.” He continues, saying old mining camps are becoming orchards and vineyards. Rude cabins are being replaced by “vine-clad cottage[s].” Oleanders bloom “before doorways” where before there was only the noxious poison oak.

“Yet it is a relief to get out of sight of the crater like chasms left by the miner, with their pinky chalk cliffs of ancient drift, along which the cars fly as over a parapet or wall. It is pleasant to quit the hills denuded of timber and left so desolate in their dusty brown ; delightful to reach loftier ridges and plunge into cool shades of spicy pine. Here nature seems to reassert herself as in the time of her unbroken solitude, when the trees grew, and flowers bloomed, and birds caroled ; when the bright cataracts leaped in song, and the hazy canon walls rose in softened grandeur, indifferent to the absence of civilized man” even though it’s civilization that has given us access to the beauty via the railroad.

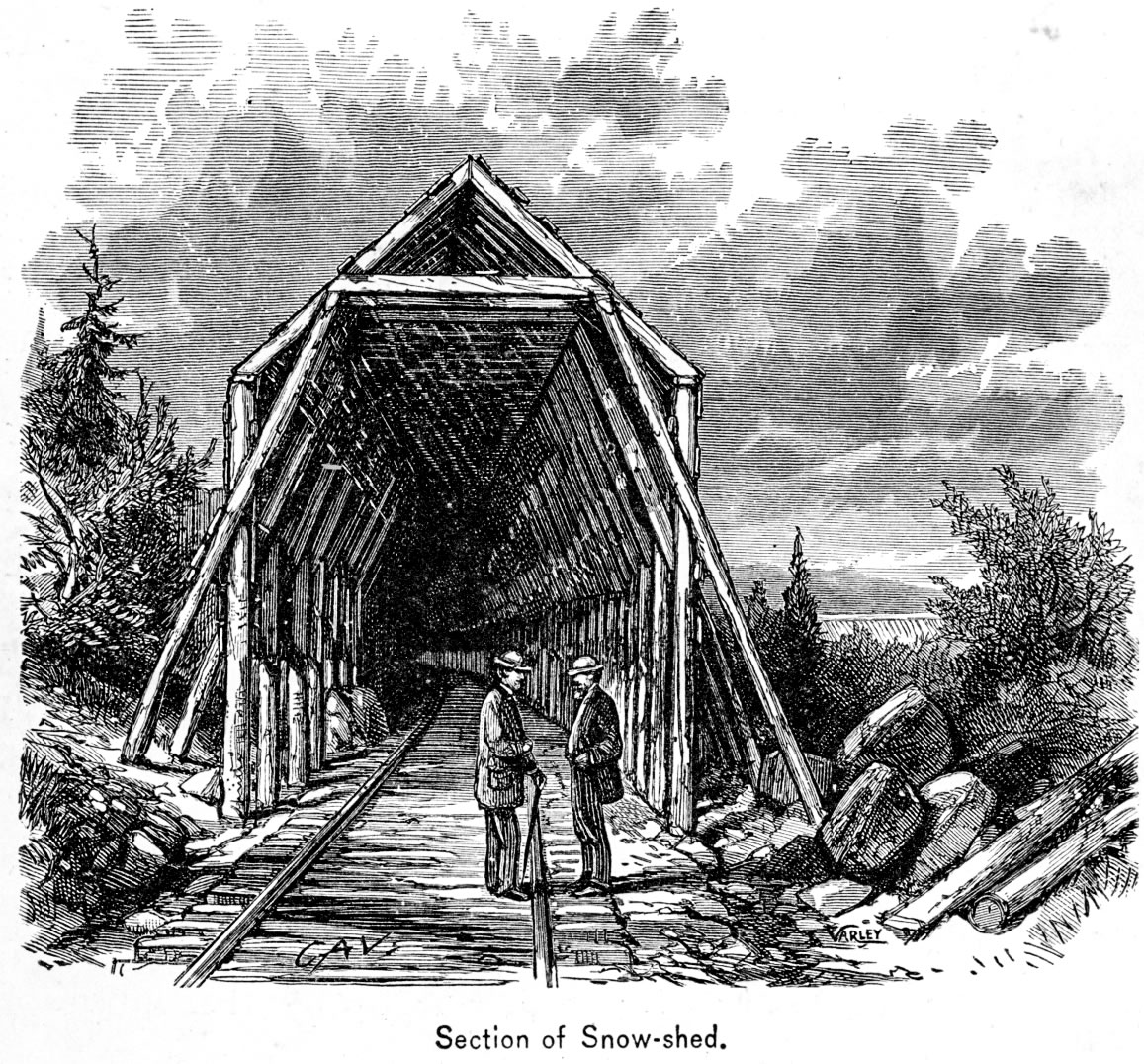

“Flying over deep gulches on trestles one hundred feet high, and along the verge of canons [sic] two thousand feet deep, we look out on the air and view the landscape as from a perch in the sky. Thus is the picturesque made easy, and thus mechanical genius lends itself to the fine wants of the soul.” And then the traveler gets to the snowsheds: “the vision of mountain scenery is cut off by the many miles of snow-sheds, or, at best, is only caught in snatches provokingly brief, as the train dashes by an occasional opening.” “Here and there in the sheds are cavernous side-openings, which indicate snow-buried stations or towns, where stand waiting groups of men, who receive daily supplies — even to the daily newspaper — in this strange region. The railroad is the raven that feeds them. Without it these winter wildernesses would be uninhabitable. When the train has passed, they walk through snow tunnels or smaller sheds to their cabins, which give no hint of their presence but for the shaft of begrimed snow where the chimney-smoke curls up. And in these subnivean abodes dwell the station and section people, and the lumbermen, during several months, until the snow melts and its glaring monotony of white is suddenly succeeded by grass and flowers…”

“Nothing can be more charming than the woods of the Sierra summit in June, July, and August, especially in the level glades margining the open summit valleys, at an elevation of from six thousand to seven thousand feet. The pines and firs, prevailing over spruces and cedars, attain a height ranging from one hundred to two hundred feet, and even more. Their trunks are perfectly straight, limbless for fifty to a hundred feet, painted above the snow-mark with yellow mosses, and ranged in open park-like groups…”

“To the citizen weary of sordid toil and depressed by long exile from nature, there is an influence

in these elevated groves which both soothes and excites. Here beauty and happiness seem to be the rule, and care is banished. The feast of color, the keen, pure atmosphere, the deep, bright heavens, the grand peaks bounding the view, are intoxicating. There is a sense of freedom, and the step becomes elastic and quick under the new feeling of self-ownership. Love for all created things fills the soul as never before. One listens to the birds as to friends, and would fain cultivate with them a close intimacy. The water-fall has a voice full of meaning. The wild rose tempts the mouth to kisses, and the trees and rocks solicit an embrace. We are in harmony with the dear mother on whom we had turned our backs so long, yet who receives us with a welcome unalloyed by reproaches. The spirit worships in an ecstasy of reverence. This is the Madonna of a religion without dogma, whose creed is written only in the hieroglyphics of beauty, voiced only in the triple language of color, form, and sound.

That’s all prelude to arriving at the Summit, “Arrived at the summit of the Sierra Nevada, on

the line of the railroad, there are many delightful pedestrian and horseback excursions to be made in various directions.” Avery arrived at the Summit Valley which he says was associated with the “tragically fated Donner emigrants.” (The rescuers of the Donner Party and the rescuees all traveled Summit Valley and somewhere in the neighborhood was Starved Camp (see the June, ’18 Heirloom).

Compared to the natural scenery the summit was not attractive. There was “an odious sawmill, which has thinned out the forests ; an ugly group of whitewashed houses ; a ruined creek, whose waters are like a tan-vat ; a big sand dam across the valley, reared in a vain attempt to make an ice pond ; a multitude of dead, blanched trees ; a great, staring, repellant blank…”

It wasn’t completely “unlovely” though because there was still a green meadow leading to the base of peaks ten thousand feet high “whose light gray summits of granite, or volcanic breccia, weathered into castellated forms, rise in sharp contrast to the green woods margining the level mead.” The glacial erratics in Summit Valley, “the boulder-strewn earth reminds one of a pasture dotted with sheep.”

One of the nearby peaks is Castle Peak “Its volcanic crests is carved into a curious resemblance to a ruined castle.” [sic] Avery says you can start the climb on horseback and then must resort to climbing “afoot.” The final slope is arduous, steep, and covered with “sliding debris” which anyone who has climbed Castle Pk. can attest to is still the experience. At the top the effort is repaid with a “superb view, embracing at least a hundred miles of Sierra crests… Including the flashing sheet of Tahoe.”

Finishing with the summit Avery goes on to describe Plumas, Shasta, Lassen, an experience on the stage, fishing ( one summer a guy caught 3,182 trout using salmon eggs), the Geysers, San Francisco, Monterey, and the Native Americans (including the petroglyphs at Summit Soda Springs).

Of course for the Heirloom reader the descriptions of Donner Summit are the most interesting but a close second is San Francisco in 1878. Today as we enter the Bay we’d describe the bridges, skyscrapers, and the wharfs along the waterfront along with maybe Giants stadium. Avery visited in 1878 though, and he saw a different San Francisco, “There is some beauty of form in the

deeply eroded sandstone hills along the ocean where the surf dashes and roars constantly, and some richness in their tints of brown rock and yellow stubble under a summer sun and clear sky. There, as the ship enters a narrow strait leading to the bay, bold rocky cliffs on one side, a tall mountain on the other…” Then from the top of Nob Hill, “Returning again to our hill in the city, one overlooks

the undulations of the metropolis all around him, and has a vivid sense of the abounding energy,

increased by the stimulus of a dry and equable climate, which created the place from nothing.” Looking west, “The noisy town on one side, and the still blue Pacific on the other, of these thousands who have gone before, are apt emblems of the lives they led, and the peace they have found. The city thins into scattered hamlets, that are lost in drifting sand ; and beyond one sees the ocean, hears the faint roar of its surf… Among the sand, on every hand are hillocks of green shrubbery with intervals [sic] of grass, hollows filled with ceanothus thickets and groves of stunted live-oak, and even a lakelet or two, where a great park is in progress of creation.”

It’s a bit different now.

“California Pictures…” is a fun book to peruse if you like words. I can’t imagine my guy in New York (See the second paragraph above) staying in his study when a ten day train ride would have taken him to California.

Drop quotes:

Lake Tahoe

“The most extensive and celebrated of the whole group is Lake Tahoe, in El Dorado County, only fifteen miles southwardly from Donner Lake and the line of the Central Pacific Railroad.

Its elevation above the sea, exceeding six thousand feet; its great depth, reaching a maximum of more than one thousand five hundred feet ; its exquisite purity and beauty of color ; the grandeur of its snowy mountain walls; its fine beaches and shore groves of pine, — make it the most picturesque and attractive of all the California lakes. Profound as it is, it is wonderfully transparent, and the sensation upon floating over and gazing into its still bosom, where the granite boulders can be seen far, far below, and large trout dart swiftly, incapable of concealment, is almost akin to that one might feel in a balloon above the earth. The color of the water changes with its depth, from a light, bluish green, near the shore, to a darker green, farther out, and finally to a blue so deep that artists hardly dare put it on canvas. When the lake is still, it is one of the loveliest sights conceivable, flashing silvery in the sun, or mocking all the colors of the sky, while the sound of its soft beating on the beach is like the music of the sea-shell.”

Snowsheds

“These sheds, covering the track for thirty-five miles, are massive arched galleries of large timbers, shady and cool, blackened with the smoke of engines, sinuous, and full of strange sounds. Through the vents in the roof Standing in a curve the effect is precisely that of the interior of some old Gothic cloister or abbey hall, with the light breaking through narrow side windows. The footstep awakes echoes, and the tones of the voice are full and resounding. A coming train announces itself miles away by the tinkling crepitation communicated along the rails, which gradually swells into a metallic ring, followed by a thunderous roar that shakes the ground ; then the shriek of the engine-valve, and in a flash the engine itself bursts into view, the bars of sunlight playing across its dark front with kaleidoscopic effect… The approach of a train at night is heralded by a sound like the distant roaring of surf, half an hour before the train itself arrives ; and when the locomotive dashes into view, the dazzling glare of its head-light in the black cavern, shooting like a meteor from the Plutonic abyss, is wild and awful.”

“These sheds, covering the track for thirty-five miles, are massive arched galleries of large timbers, shady and cool, blackened with the smoke of engines, sinuous, and full of strange sounds. Through the vents in the roof Standing in a curve the effect is precisely that of the interior of some old Gothic cloister or abbey hall, with the light breaking through narrow side windows. The footstep awakes echoes, and the tones of the voice are full and resounding. A coming train announces itself miles away by the tinkling crepitation communicated along the rails, which gradually swells into a metallic ring, followed by a thunderous roar that shakes the ground ; then the shriek of the engine-valve, and in a flash the engine itself bursts into view, the bars of sunlight playing across its dark front with kaleidoscopic effect… The approach of a train at night is heralded by a sound like the distant roaring of surf, half an hour before the train itself arrives ; and when the locomotive dashes into view, the dazzling glare of its head-light in the black cavern, shooting like a meteor from the Plutonic abyss, is wild and awful.”