Snow Is Not a Problem on Donner Summit

That’s kind of what Theodore Judah said. Judah was chief engineer for the Central Pacific Railroad and laid out the route over Donner Summit. Mt. Judah is named for him (the Judah Loop is a GREAT hike – the views are spectacular).

Judah had studied the trees on the summit and noted where the moss started growing. He thought that was as high as the snow went and since the snow would not all fall at once he was sure the railroad could just push the few inches that fell at any one time, out of the way.

Donner Summit gets an average of 34 feet of snow each winter. In some years more than fifty feet fall. The first Winter they were building the tunnels, 1866, there were 44 storms and 60 feet of snow fell. The ski areas were probably very happy. Snow falls on Donner Summit in feet, not inches in a normal winter.

Not only does a lot of snow fall but the snow on Donner Summit is affectionately called “Sierra Cement.” It is really heavy.

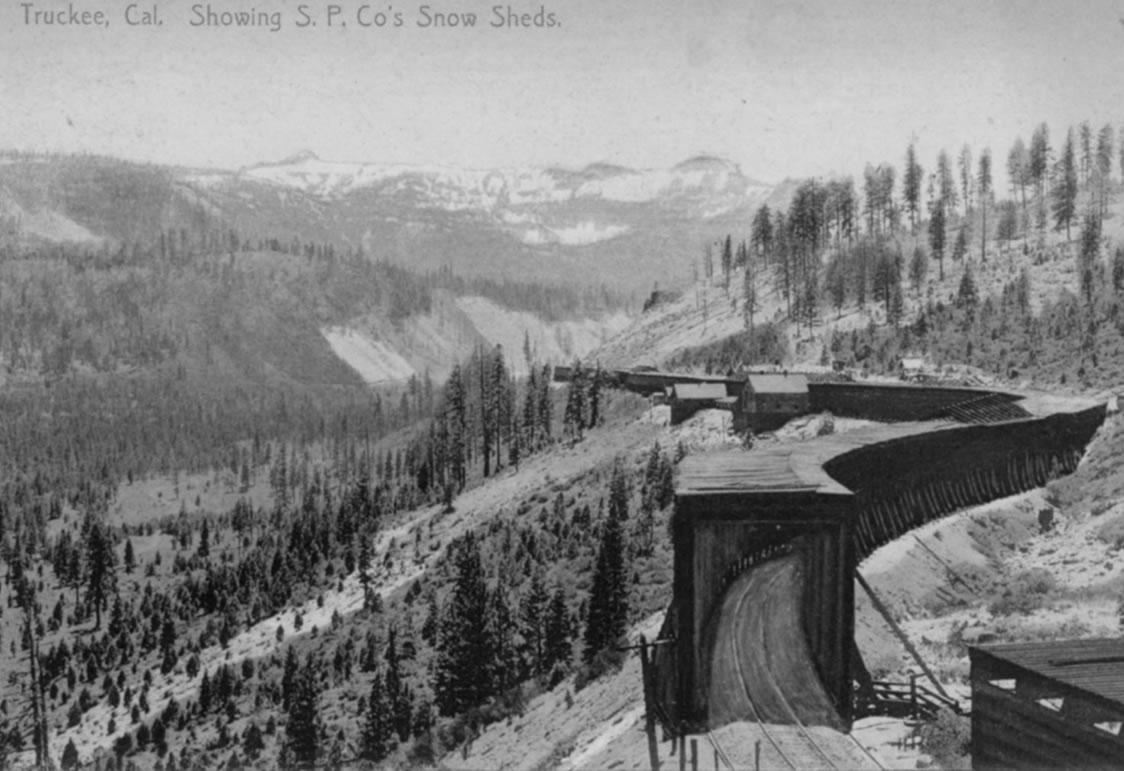

Even before the railroad was completed in 1869, the builders started building snowsheds to protect the track and eventually 40 miles of sheds were built. The sheds became an iconic symbol of Donner Summit.

In the picture above you can see the snowsheds stretching across the center of the photograph, across the face of Donner Peak.

Snowshed Stories

The snowheds are, except for the scenery, the most recognized feature on Donner Summit and so there are lots of stories having to do with the sheds.

Circus Train Wrecks

One night in 1904 a circus train decoupled just east of the summit., As the locomotive continued blithely along, not knowing it had lost the circus, the circus cars stopped and then began to go backwards. As they gained speed they derailed and many animals got out. No one knew it had happened until a railroad worker, heading home after work, came across a tiger in the snowsheds. He ran in the opposite direction. A couple of lions were retrieved from the forest and monkeys from the snowshed rafters. A snake charmer had to be brought in to get a boa to come down from the timbers it had gotten into.

Bicycle in the Sheds

Bicycle in the Sheds

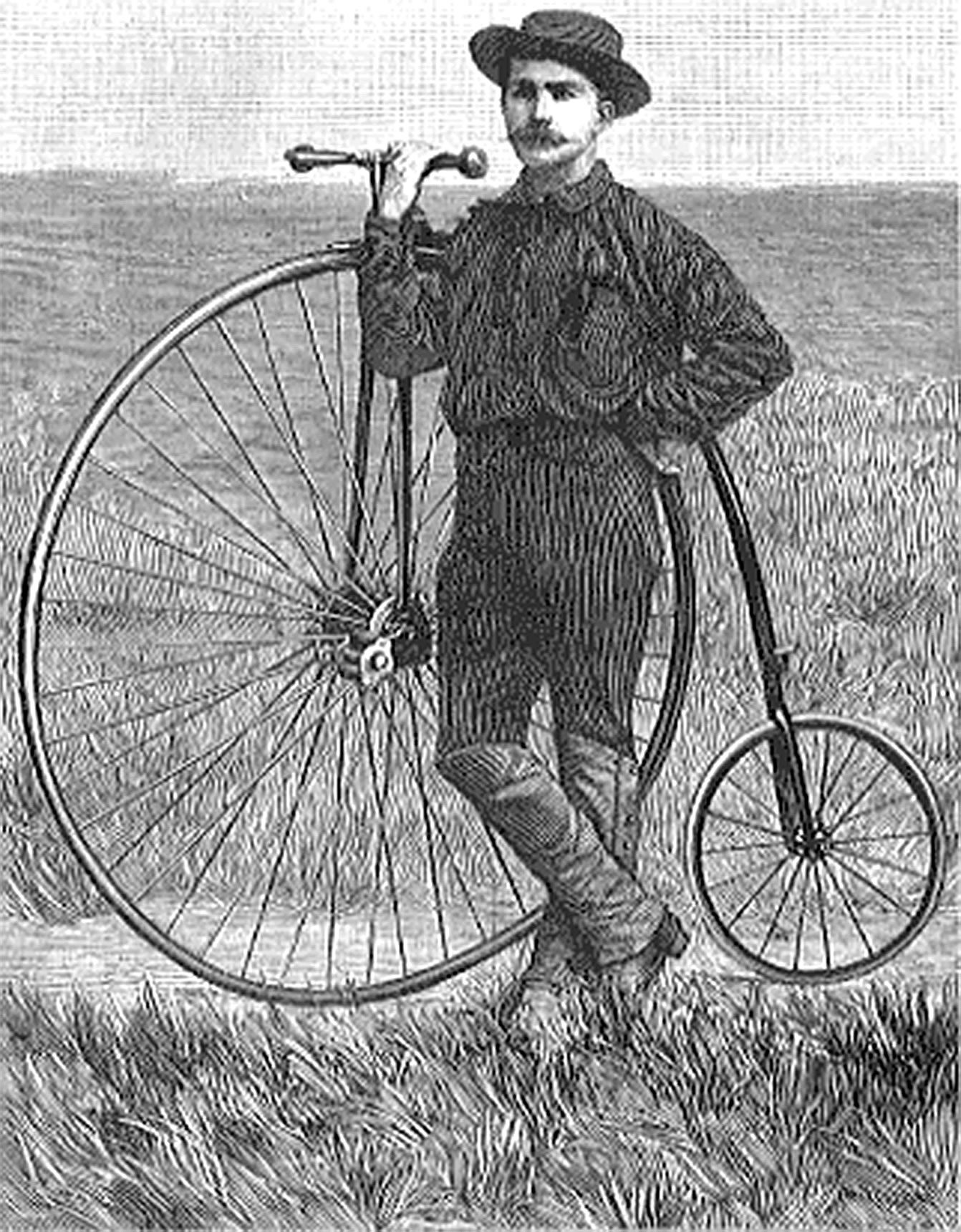

Thomas Stevens, right, the first bicyclist to cross the summit (1884) had started in April, a time when many feet of snow still cover the ground on Donner Summit. He had to push his high wheeler through all forty miles of snowsheds. That’s him and his bicycle above.

Stevens said it was not “pleasant going” as he groped his way through the gloomy interior. When he heard a train he’d “proceed to occupy as small an amount of space as possible” against the side, and wait for the “smoke-emitting monsters” to pass. The engines “fill every nook and corner of the tunnel with dense smoke, which creates a darkness by the side of which the natural darkness of the tunnel is daylight in comparison. Here is a darkness that can be felt...” He survived.

When the sheds were reconstructed of concrete there was a lot of snowshed timber lying around and a number of enterprising Donner Summit residents collected it and built houses and lodges from them. One Summit resident remembers her mother spending an entire summer sanding the accumulated smoke from their house’s new walls. Today the interior of that house is gorgeous, warm and inviting.

First Motorized Crossing

First Motorized Crossing

The first motorized crossing of Donner Summit was done on a motor bicycle in 1903. George Wyman (left) also pushed his vehicle through the sheds.

The Mole People of Donner Summit

Snowsheds at one time connected almost all the buildings on Donner Summit. Kids walked through the sheds to school. The front door of the Summit Hotel connected to the sheds. There were stores, stables, and other businesses in the sheds. “Fong’s,” a restaurant, was inside the shed at Norden.

There is so much snow in Winter and there were so many sheds that some workers did not see sunlight for months at a time. The San Francisco Chronicle dubbed them the “Mole People” of Donner Summit.

A Job Like No Other

The wooden sheds leaked, a lot. The dripping water would form huge icicles that had very interesting shapes. Thomas Stevens (previous page) saw “whole menageries of animals. all imaginable objects reproduced in clear crystal ice…” no doubt partly due to the boredom of traveling 40 miles through the dark.

The icicles created a hazard for train cars so the railroad employed a person to walk the sheds with a shotgun to blast away offending ice.

Telescoping Sheds

Telescoping Sheds

To prevent fires from spreading spaces were needed in the long line of snowsheds and so telescoping sheds (right) were built. In summer one section of shed was rolled into another leaving a firebreak.

Snowshed Problems

Snowsheds kept the transcontinental railroad line open and so were a huge benefit. They also had problems.

Snowsheds collapsed regularly under the heavy mountain snows and avalanches. Hundreds of railroad workers were on hand to keep the roofs clear of snow.

Snowsheds had to be continually rebuilt because railroad equipment kept getting bigger.

The biggest problem was snowshed fires.

Snowshed Fires

The snowsheds provided the solution for the heavy snows of Donner Summit but they also were a problem. Today the sheds are all concrete but the first ones were made of wood that would bake all day in the summer sun. The steam locomotives emitted sparks. Sparks and tinder dry wood are not a good combination. In addition the sheds acted like chimneys drawing in air that would just increase a fire’s intensity. Conflagrations resulted as miles of sheds burned at a time.

A New Zealand newspaper reporting on the unique snowsheds saying, “…a more convenient arrangement for a long bonfire I never saw.” Hawke’s Bay Herald January 28, 1870 (the railroad was finished in 1869.)

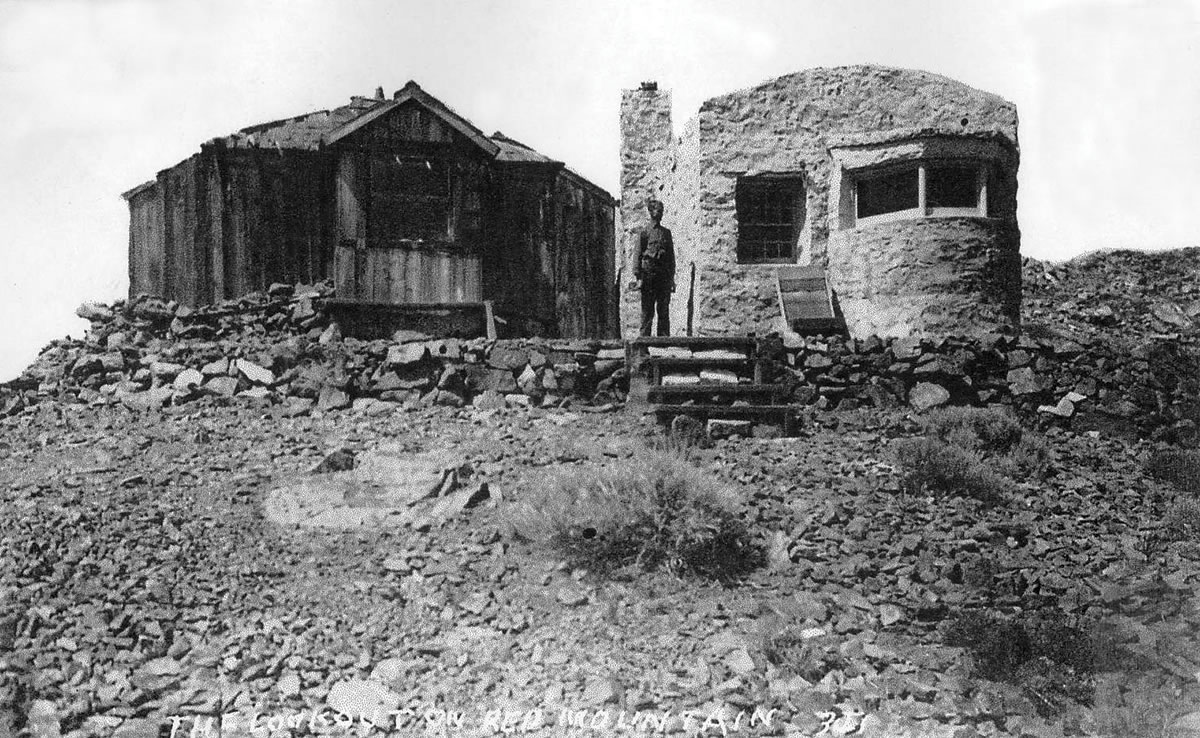

To combat the problem the railroad built an observation building (left) on Red Mountain (the building is still there and Red Mountain is another marvelous hike with extraordinary views) manned by two observers. From Red Mountain they could see almost all of the sheds. When a fire was spotted the spotters would pick up the first telephone installed in California and call Cisco. Cisco would telegraph the fire trains that were always kept ready with full heads of steam. The fire trains would speed to the fires.

Great Views Except That....

The views on Donner Summit are spectacular so a train crossing the summit could offer its passengers a wonderful experience.

Unfortunately the original 40 miles of snowsheds shut off the great views to the traveling public. In addition all the locomotive smoke was not exhausted by the shed chimneys and the sheds would fill with smoke.

The San Francisco Call said in 1905 that “THE average passenger journeying over the Sierras usually utters a deep sigh of relief -when his train emerges from the snowsheds. They have formed one bleak, uninteresting section of the journey, relieved only by a monotonous succession of tantalizing glimpses of striking scenery through the breaks and cracks in a dead wall of grimy timbers. The cars have filled with suffocating smoke and life has been made miserable for a time.”

Bucker Plows

Although there were 40 miles of snowsheds there were plenty of miles of track that were not protected by the sheds. To remove the snow on that track the railroad used bucker plows. They were huge, up to 40,000 pounds, and would be pushed by up to 10 locomotives. A bucker plow could charge into drifts at up to 60 miles an hour, but the snow, the “Sierra Cement,” would still stop it cold. The plow would then back up (assuming it had not become stuck), go forward gaining speed, and smash into the snow again. Eventually the track would be cleared. That’s a bucker plow at right.

Although there were 40 miles of snowsheds there were plenty of miles of track that were not protected by the sheds. To remove the snow on that track the railroad used bucker plows. They were huge, up to 40,000 pounds, and would be pushed by up to 10 locomotives. A bucker plow could charge into drifts at up to 60 miles an hour, but the snow, the “Sierra Cement,” would still stop it cold. The plow would then back up (assuming it had not become stuck), go forward gaining speed, and smash into the snow again. Eventually the track would be cleared. That’s a bucker plow at right.

Below, the snowsheds on Donner Summit. The white building to the left is the old Summit Hotel in its first incarnation. The peaked building houses the turn table used to turn the helper engines around. Trains needs helper engines to get up the mountains in the old days. The shed in the bottom center leads off to Tunnel 6.

Looking for a snowshed job?

NEVADA – NEVADA RENO – TRUCKEE- DIVISION

Summit, Tamarack, Cisco. Placer, etc.

250 carpenters and carpenters’ helpers

for work on the great snow sheds,

$60 to $90 month

FREE FARE – SHIP DAILY

San Francisco Call October 1, 1907